Being Right vs Getting It Right: A Commentary on Scouting and Process in the Pursuit of Winning

The past couple of weeks, I have had one phrase stuck in my head, which was said to me in an argument on Twitter one time by former Nebraska Football player and current analyst Damon Benning, and that’s this: “You’re worried about being right & not getting it right.” Now, let’s throw away the horrors of the Nebraska one-score loss to Maryland that day and the emotions that went into me getting into a tiny little argument about terminology on a playcall with someone way smarter than me in that area, and look at how so often I see comments, takes, and opinions on players that could learn from this statement.

Frequently do I think people get caught up in what they think a basketball player is supposed to look like, or on the other hand, the analytical profile they would want a player in their organization to have, while ignoring one side or another, or they selectively choose aspects from one or another without having a true concret philsophy of whay they want a basketball team to look like. But what is my process?

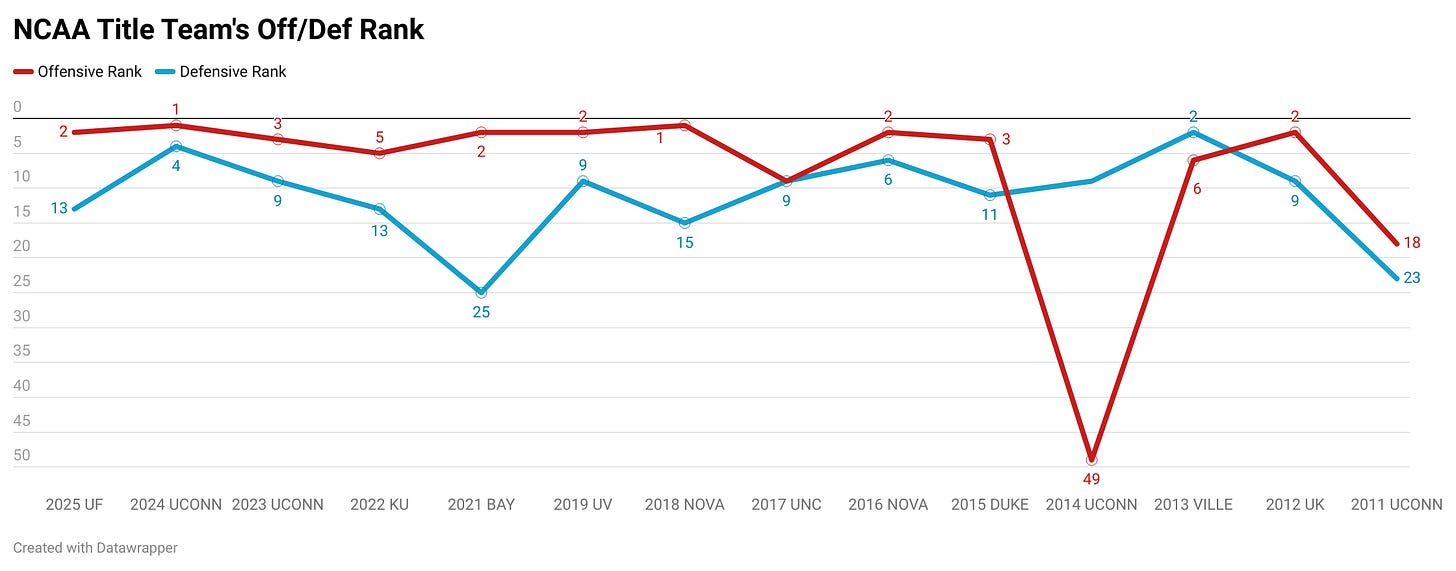

What I look for in a player isn’t necessarily concrete. I don’t believe there is one all-encompassing way that an NBA or NCAA team should be playing, but there are some general principles I adhere to when evaluating players. For one, I believe that offense is generally more valuable to cater to than the defensive side of the ball. Throughout modern basketball history (which I am going to artificially cut off at LeBron going to Miami), most championship NCAA teams are elite offenses with enough of a floor to maintain great or elite production on that side of the floor. Per Barttorvik, every single NCAA champ dating back to 2015, barring a 2017 North Carolina squad that ranked 9th in both offense and defense, has ranked higher in their offensive rank compared to defense.

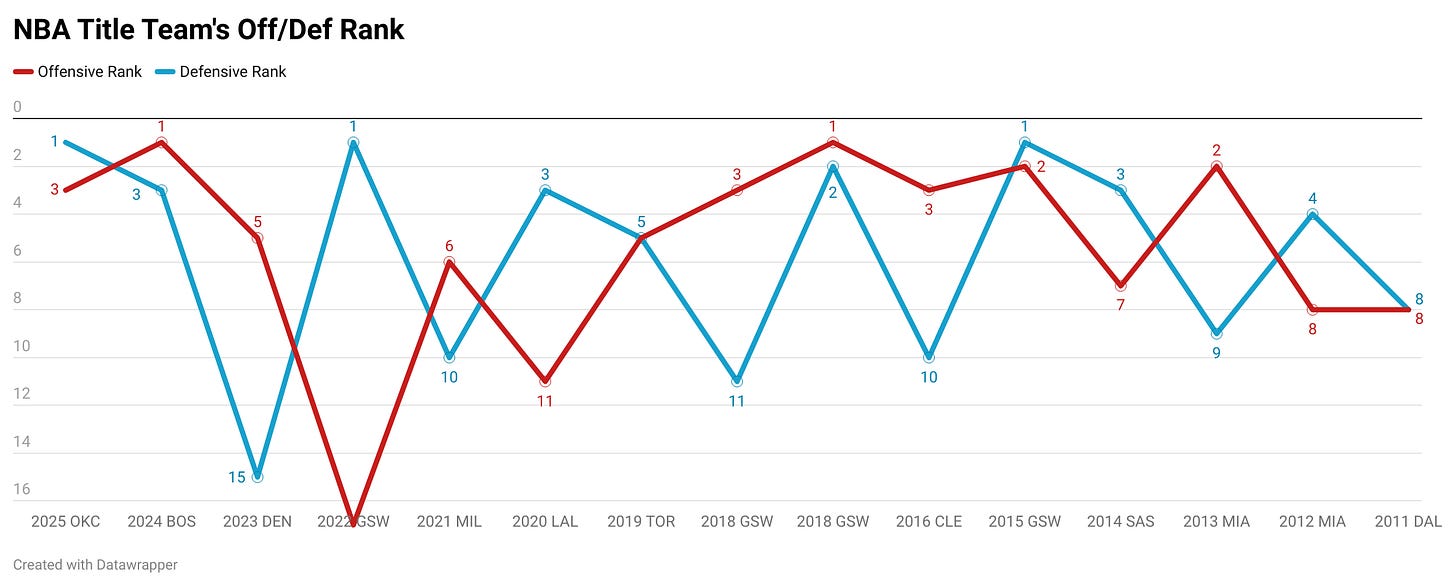

In the NBA, this trend doesn’t hold as well, with a much closer to a 50/50 split in teams’ rankings in offensive and defensive ratings, but it still generally leans towards needing an elite offense to win an NBA title.

However, the crux of winning an NBA title is by having one of the 5 best players in the world at a time, and generally these 5 best consensus players are also 5 of the 8-10 best offensive players in the world. Without one of these forces, it is impossible to win an NBA title, with the 2004 Pistons and 2014 Spurs really being the only example of a team winning without a top 5 player in recent memory, and even that Spurs team has Kawhi as an argument as the best defender on the planet, who was also additive on offense. Despite this balance of offense and defense in metrics, getting offensive production from stars in a playoff setting is generally more important than star defensive production. Since the 2014 Spurs, the best player on each team to win a championship has never ranked lower than 97th percentile on Offensive-EPM, with Kawhi Leonard and Giannis Antetokounmpo being the two to accomplish this feat of 97th rather than 98th-100th percentile, and the pair are also two of the four players in league history to win Finals MVP and a DPOY in their career.

Finding this level of offensive production is vital to winning a championship at the NBA level, and finding not only these apex predator offensive stars but finding the role players who complement them and fully maximize their creation potential is something I find more valuable than finding defenders at the NBA level, despite no correlation between offensively slanted teams or defensively slanted teams. Most NBA Champions are both top offenses and defenses, and finding players who contribute to both is what is really important.

For that reason, I believe it is more viable to evaluate college prospects as chess pieces and NBA prospects as consistent rotation players who need to be able to play 20 minutes in the playoffs on any given night. It is more viable for someone like LJ Cryer, for example, to be a key contributor on multiple top-ranked Baylor and Houston rosters, as his defensive limits due to his size and inability to generate shots at the rim are far less limiting in a game with less margins for error in a single night. In a collegiate game with less dominant primary creators to drag out the best matchups one-on-one, or slower and less snappy schemes, offensive slanted players are possible. These offensively slanted players can then make up for defensively slanted players at the college level, like another Houston player in Jojo Tugler, last season. Tugler doesn’t space the floor, is slightly undersized as a big man play finisher, doesn’t create, and offers little offensive value outside of offensive rebounds. Still, he was my bet as the best defender in all of college basketball last season, and the push-and-pull dynamic of Cryer and Tugler on the floor together can work, as evidenced by the two actually being +10 as a lineup combo compared to Houston’s normal Net Rating in the 2025 season.

In the NBA, you have to stay consistent and play on both ends, with rare occasions of bringing truly one of a kind value on one end, or you will get played off the floor, whereas in college, you can prosper with a more narrow player or archetype.

Arguably more important than any of the skills or tools any prospect can have is the person behind the jump shot or dunk. This last summer, when I spoke to Matt Painter for a brief period of time about what he looks for in players, he told me to forget any of the obvious scheme stuff and pay attention to how good a teammate, worker, learner, and, most importantly, competitor someone is. A young 18-22-year-old heading from high school to college or college to the NBA can fail based on the fit or readiness just as much as they can based on the skills. If you are trying to make a peanut butter and pickle sandwich, it doesn’t matter how good the pickles are; it’s going to be bad. The fit of a group of players and willingness to execute a scheme are just as important. It is better to have 5 players executing one suboptimal vision in unison rather than them tugging away in different directions.

It is also important to understand the developmental situation a player is walking into when they draft them. Right now, as a general scout and I suppose someone you could count as “media,” as well as most reading this, have the curse of ranking each player in a vacuum. Unlike NBA teams, media members and internet scouts rank every player based on how much value they think a player will and can return. The problem I often face with some players is that I think in certain contexts they might be great, and in others, they might end up being a disaster.

For example, I had Kel’el Ware ranked #38 on my 2024 Big Board. Below, I will put my explanation from that cycle as to why I was lower on the Indiana Big:

Ware is an absolute freak of a man. This pops on tape, and he is MASSIVE in person. I get it. The gifts are amazing. He doesn’t just move well or jump high or have long arms, he also has great touch, among other things, but frankly, I just don’t buy Kel’el Ware the competitor. This is something that has been widely discussed for Ware, as coach Dana Altman at Oregon repeatedly called out Ware for his effort when he was there as a freshman, and while it improved at Indiana, the processing and overall motor still showed as a negative this season, and let me tell you, this just scared me in person. Possession after possession, Ware repeatedly was out of position on defense, and because it’s college basketball and he is by far the best athlete on the floor, he was consistently bailed out by his gifts. In the NBA, everyone, including other bigs, will be just as athletic as Ware, if not more athletic, and they don’t have this processing issue. He has this long wingspan, but in drop coverage, his hands were never in the right place. He also isn’t very strong in his core and struggles with contact. On offense, he is a quality 1 on 1 post scorer and roll man, but all season, if Ware was doubled or his first option was dealt with, he panicked, and he doesn’t possess the feel to make the right read or counter. He never really initiated contact, and I don’t love a lot of the footwork out of ball screens. This leads to him getting in the short roll area, where he again panics and throws up an awful shot most of the time. I fully acknowledge that of all my grades in this draft, this is probably the most likely to blow up in my face. Ware jumps off the screen on tape, and in person, he might be more impressive, but I am just not sure if he can play in the NBA due to his effort, ferocity, and processing.

Even at the time, I knew that this ranking could go badly, and so far it has. Ware has had a great start to his career, not only having a good rookie season in Miami, but also a good preseason the past couple of weeks, which makes me now think he could end up becoming a very valuable starting center one day. But at the same time, I am not sure I could’ve ranked Ware any higher, and that is simply because for the majority of the teams in the NBA, I would not have drafted Kel’el Ware. I even wrote how the Heat would likely prove me wrong in my post-draft night reactions:

If anyone can fix Kel’el Ware, it’s the Miami Heat. We all know Coach Eric Spolstra and Team President Pat Riley are absolute masterminds of basketball, but most importantly, good motivators. If anyone can get the most out of the former 5-star recruit, it is likely those two. Ware will have to get his basketball IQ up, and the vigorous Heat system and offseasons of legend are the place to do so. If Ware wants to stay in the league, learning how to improve his focus under “Heat Culture” is where he should want to be.

The lesson I learned here is that sometimes it is ok to be wrong. Maybe I didn’t miss anything in my evaluation of Kel’el Ware. In hindsight, I probably should’ve respected the tools more despite some of the process deficiencies and ranked him higher, but if I were the Miami Heat, I wouldn’t have had Kel’el Ware near the top of my board for the slot and understood that getting Ware in the facility would be a good move.

And this is why getting it right instead of being right is important. Sure, I look kind of stupid when you go look at my board, and I had Ware outside of the top 30, but at the same time, I learned something and got the process right.

So, what am I looking for going into this cycle from an NBA perspective? The answer, and what it has been for me over the past two years, is positive contributors in a playoff setting. I am looking for players who row both sides of the proverbial boat that a championship team is, meaning that even if you aren’t rowing each side the same as I would prefer, you are at least not vastly slowing down that side of the ball.

As always, quick processors are valuable. Last year’s finals runs from both the OKC Thunder and Indiana Pacers showed this more than ever, as “0.5 basketball” led by quick decision making will almost always reign supreme over poor processing on the floor. That goes for star bets as well, as there is a threshold you must reach as a passer to survive as a shot creator in the playoffs.

That being said, there isn’t some passing threshold or “high feel” statistically threshold I am looking for. One thing that the Indiana Pacers’ recent run has made me realize is how good that franchise in particular is at addressing market deficiencies in players. They got Obi Toppin, a former lottery pick, for nearly free, turning his post-up game in college into one filled with transition production, cutting, and corner shooting. They took a throw-in to the Malcom Brogdon trade in Aaron Nesmith and turned him into Klay Thompson-lite, with him arguably being the 3rd best player on a team to take an all-time great Thunder squad to Game 7 of the finals.

Both of these players would likely fit the analytical “low-feel” threshold, with neither passing at a high rate in college or the NBA, primarily being play finishers, but with the Pacers front office and Head Coach Rick Carslile having the vision to turn these players into chesspieces in an offensive system with arguably the highest decision threshold in the NBA has shown their value. Simply, it can be summed up to finding players who play winning basketball, which is absolutely a buzzword that gets thrown around, but it’s really the only term that works. What I hope to have illustrated is that a winning basketball player doesn’t fit a certain shape, size, or Barttorvik query.

great article. As someone who's been in the scout space for a while, I have had my fair share of idiotic takes.

All I will say is that has led to a lot of growth from me.

This year, when working on my statistical draft model, I have edited it at LEAST 5-6 times unexpectedly to make sure that specific areas aren't overvalued/undervalued. The draft is HARD and it's OKAY to get things wrong.